Introduction

If you want to build a mobile app, React Native is a great choice. Many advantages would make you pick this technology over others: reusing React Web devs, hybrid development, and the JavaScript community are just some of them.

However, it is often said that the performance of apps developed with React Native is the framework's greatest disadvantage. This notion probably stems from the belief that native development is always the most performant option. However, it is important to note that in many cases, the benefits of hybrid development outweigh the minimal performance losses (which are often hardly noticeable).

In 2022 React Native's new architecture introduced changes that aimed to turn this performance situation around. But does it truly? How does it compare to the old architecture? To test this, I'll compare two RN apps, one of them built using the new architecture and the other one using the old architecture. We'll evaluate them regarding app size, open time, animations, big lists, and navigation transitions.

Let's begin!

The Usual Suspects of Low Performance

A culprit of poor performance that is often pointed out is the bridge. In the previous architecture of React Native, the bridge acted as a communication channel between the JavaScript thread and the native thread. It was often considered a bottleneck because of the way it shared data between these threads. If you're interested in learning more about how the bridge used to work, you can find further details here.

However, with the introduction of the new architecture, the bridge has been eliminated, making way for a new communication mechanism called the JavaScript Interface (JSI). This significant change is expected to enhance performance, but does it?

By testing out React Native's new architecture through two apps, we'll be able to see if it offers any performance improvements. Although both apps are absolutely similar code-wise, one was built using the old architecture, and the other one using the new architecture. The aim of this comparison is to see if there is a noticeable difference between both.

I'll be running the apps on a Samsung J3, an old low-end Android device. Why, you might ask? Because on a new iPhone, almost anything will work like a charm thanks to its powerful hardware. However, this is not the case for many Android devices, which have more limited resources, but also lead the market, holding over 70% of mobile users in 2023 (source). It is safe to assume that many of those devices are mid-range or low-range, so it is important to enhance the experience of those users too as much as we can. Also, the differences might be more noticeable on this device, which will be useful for comparison.

It's important to note that although the architecture changes may be more noticeable on low-end devices, it doesn't mean they don't affect high-end devices. It simply means that these changes are easier to visualize and perceive on low-end devices.

App size

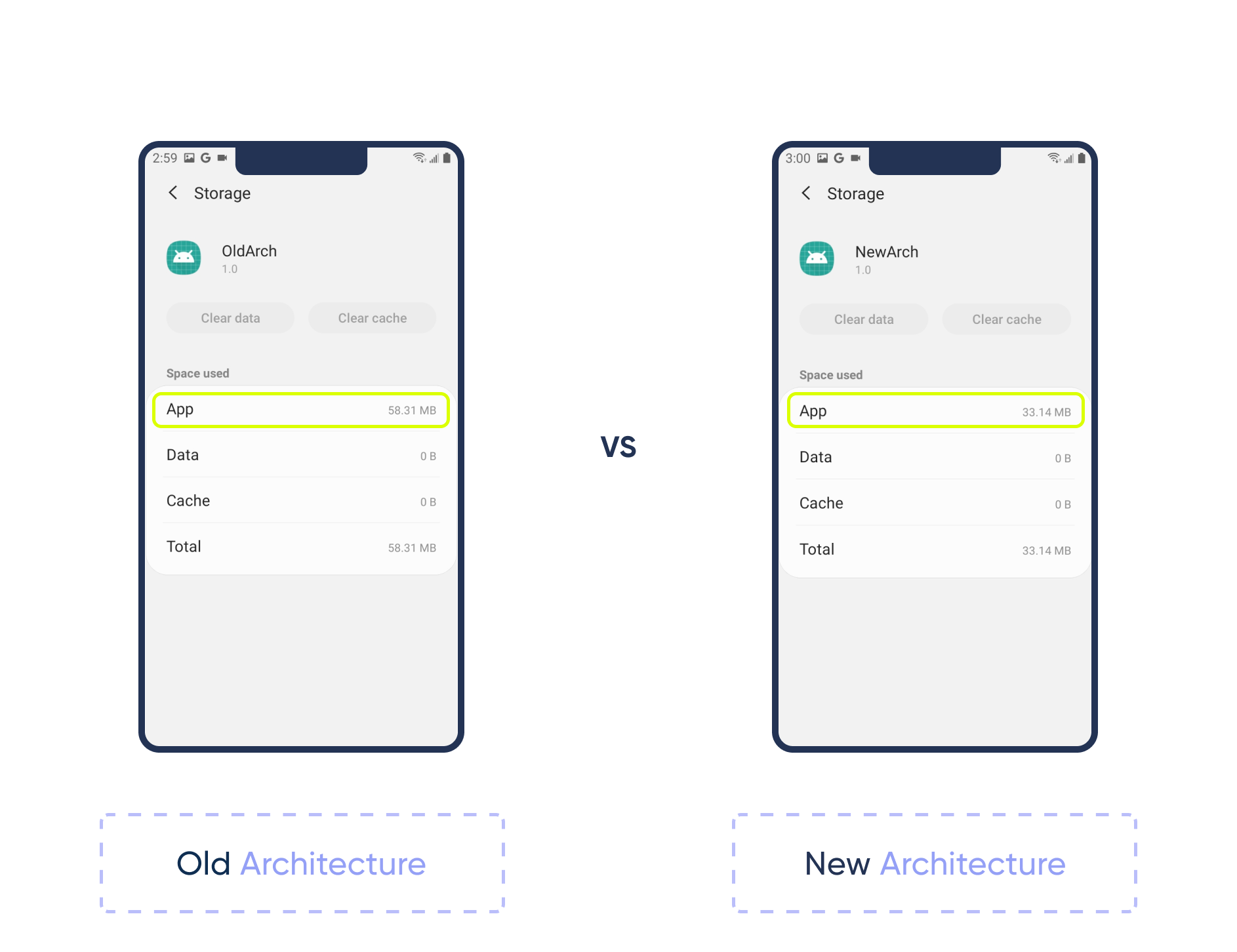

One of the first things we’ll compare is the app size. On the left, the app that was built with the old architecture, and on the right the app built with the new one.

Outcome:

The old architecture app has a size of 58.31 MB, while the new architecture app has a size of 33.14 MB.

Impact:

While app size doesn’t have a direct effect on performance, it’s interesting to compare the two apps in this regard. The difference is very noticeable, especially considering that although these two apps have exactly the same features and code, the old architecture version almost doubles the size of the new application.

App open time

To measure the app's opening time, we recorded the screen while launching the app five times and then calculated the average time.

Outcome:

The old architecture app takes, on average, 2.3 seconds to open, while the new architecture app takes only 1.5 seconds on average.

Impact:

The app open time is a very important aspect of the user experience. It is the first thing that a user will notice after downloading the app. A fast first load creates a positive impression of the app and sets the stage for a seamless user experience.

Animations

Under the hood in the test that we will perform, after pressing the button, the app shares a heavy data stream between the JS thread and the native thread. Because of the bridge, this action used to imply that you had to pay serialization/deserialization taxes. One of the big advantages of the new architecture is that now JavaScript can directly invoke functions in other threads and does not have to wait for the response if it does not need to. This means that, for example, animations won’t drop frames because of bottlenecks in the bridge.

Outcome:

The entering animation (the one where the heavy calculation is being performed) looks smoother in the app that is using the new architecture. The exit animation looks the same for both apps.

Impact:

The JS calculations no longer have an impact on animations and calls to the native side. The difference between the entering and exit animation is expected because there is no heavy calculation being done when the modal closes.

Big list

In this test, we compared lists that had many elements in both apps. Before the new architecture, sometimes scrolling quickly would lead to a blank screen because the app couldn’t finish the call to the native side on time for the rendering to be ready.

Outcome:

The new architecture app has a smoother scroll. Scrolling down, we are unable to see a blank screen in any of the apps, but the scrolling is more limited in the old architecture app (it locks the scrolling for a bit if you go too fast). In the app that was built with the new architecture, there are no blank screens while scrolling up, as opposed to the old architecture app.

Impact:

This means that the scrolling experience will see an improvement with the new architecture: smoother scroll and list items will render on time. If the device is not very good, the performance issues are likely native.

Navigation transitions

We tested the navigator transitions to see if there was a visual improvement caused by the separation of the threads and the bridge removal.

Outcome:

Navigation transitions look fairly well in both apps.

Impact:

In this case, the improvement is not as visible as in other tests we ran, but it does look a bit smoother on the new architecture app.

Conclusions

There’s a hard truth that we must accept: if you’re used to new, high-end devices, nothing a Samsung J3 does will match that. It simply does not have the hardware to do so. It’s old and has always been better known for being budget-friendly than high-performance. Even in native-developed apps, performance issues will arise.

However, in this blog, we conducted an experiment that proved the new React Native architecture can bring performance improvements and other advantages that can enhance the experience of users with devices that have similar specifications. For example, the new architecture can lead to lower app size, which is an important consideration for users who are running into storage issues.

Most of our measures were qualitative since the objective was to test noticeable differences between the two apps. If you are interested in more quantitative benchmarks, these links might be of interest:

Experiment With the New Architecture of React Native

The New Architecture Performance Benchmarks

These findings do not apply solely to low-end devices, though. The test app was very small and with limited features, but a real app has many flows, features, and capabilities. Usually, performance issues start being noticeable on big apps, and it eventually starts affecting high-end devices too. That is why these architectural improvements are such great news: they will enhance the app performance for devices in all tiers.