As a developer, you'll probably have to consume services provided by third-party code. This is true in many aspects of the trade: using a third-party library, interfacing with OS components, consuming web services. I'd even wager that in today's development environment it's highly unlikely that you won't do one of the previously listed things.

Relying on other people's code can be great: it allows us not only to manage and maintain less code, but also to rely on the community for support. It can also be challenging. Not all code is great, and not all code works like we want it to.

This post tackles how to overcome one of such challenges: a frontend app that must consume services and data from a "bad" backend. We'll look at a way to define the architecture of frontend apps to be resilient against backends that change frequently, or that don't serve structured data. Moreover, by implementing this architecture, your project will be less tightly coupled to the backend, allowing for some freedom of technical choices (keep reading to find out more!).

Motivation

Frontends, by nature, have an enormous flaw: they strictly depend on some kind of backend service (an API, microservices, or any other data provider). This is not the case always, I know, but I feel like it's the case most of the time with medium to large apps. That dependency is a blessing, but also a curse. If the backend changes its API or re-structures data in some other way, the frontend has to be refactored, there's no way around it.

With such a glaring vulnerability, one would think frontends are actively protected and secured against an unexpected third-party dependency change. Sadly, my personal experience in maintaining frontend projects has proven otherwise. This motivated us to create and document a pattern that helps us isolate our frontends as much as possible from the backend, reducing the surface of our code affected by unexpected (or even expected) changes. Let's look at what kind of issues this pattern could solve.

Let's assume we're developing a web frontend in Javascript (framework-agnostic) that communicates with a typical JSON REST API that is developed by another team over which we don't have any control. Our app is an online shopping platform (creative, right?). FYI: all these next examples have happened to me first-hand (naturally I've adapted them for this post, but the concept is the same).

Main Issues We Run Into When Integrating APIs

Key That Are Not Concise

Let's say we query our backend for products and this is the response:

[

{

"Product_Name": "Electric Fan",

"Product_Price": 30,

"Product_Desc": "Spins really fast!"

}

]

We already know these are products, we certainly don't need the Product_ prefix everywhere.

And I most certainly don't want to be using those field names all over my app, it would be extremely confusing.

And what if I've been using product.Product_Name everywhere and suddenly the backend starts serializing that field differently?

Ideally, the backend would have API versioning and release a new version with these changes, so that the frontend would have time to address it eventually.

Sadly, I've had to experience these kinds of changes in backends that don't support versioning.

To fix the issues I'll probably have to mass-replace all usages of that key, which is prone to cause bugs.

How Data is Presented

Say our products are categorized and there's a category tree of three levels (Home -> Electronics -> Fans, for example). We want to show a visual representation of the category tree, so we query the backend for it. This is a subset of the response for brevity:

[

{

"CatName": "Fans",

"SubFamily": {

"SubFamilyName": "Electronics",

"Family": {

"FamilyName": "Home"

}

}

},

{

"CatName": "TVs",

"SubFamily": {

"SubFamilyName": "Electronics",

"Family": {

"FamilyName": "Home"

}

}

}

]

The tree is inverted! Ignoring the duplication of information everywhere, this tree is very hard to process and read naturally. Also, as with field names, unexpected structural changes in data will most likely crash your app and make it unusable, and these are even harder to fix than field names!

I Don't Need all that Data

Some APIs are really generic, and are expected to be consumed by a wide variety of applications, so the information they provide is vast. But sometimes you only need two or three fields. Should I hold all that information in memory to be never used?

What Data Means

APIs tend to have their own understanding of the reality they want to model, and that's fine. The disadvantage here is that sometimes frontends that consume those APIs are forced to adapt to that reality, and base development around it. It would be ideal if frontends could have some more freedom on how they model the reality and adapt that model to the frontend's needs without requiring the backend to make changes.

Goals of the Proposed Architecture

- Adaptation of field names should be trivial.

- Adaptation of data structure should be as trivial as possible.

- Decouple frontend business logic from the backend as much as we can.

For the sake of simplicity, the code and examples we're going to see next are implemented in Javascript, but they can perfectly be implemented in any language. Also, we'll cover the happy paths (no errors or error handling), but include an afterword with some considerations about this. Let's introduce the pattern then!

The Architecture: Model-Controller-Serializer

Yes, that's the name we gave it. At least we didn't use a recursive acronym (cough, Linux, cough, GNU). Besides, it perfectly describes what the pattern introduces into the code!

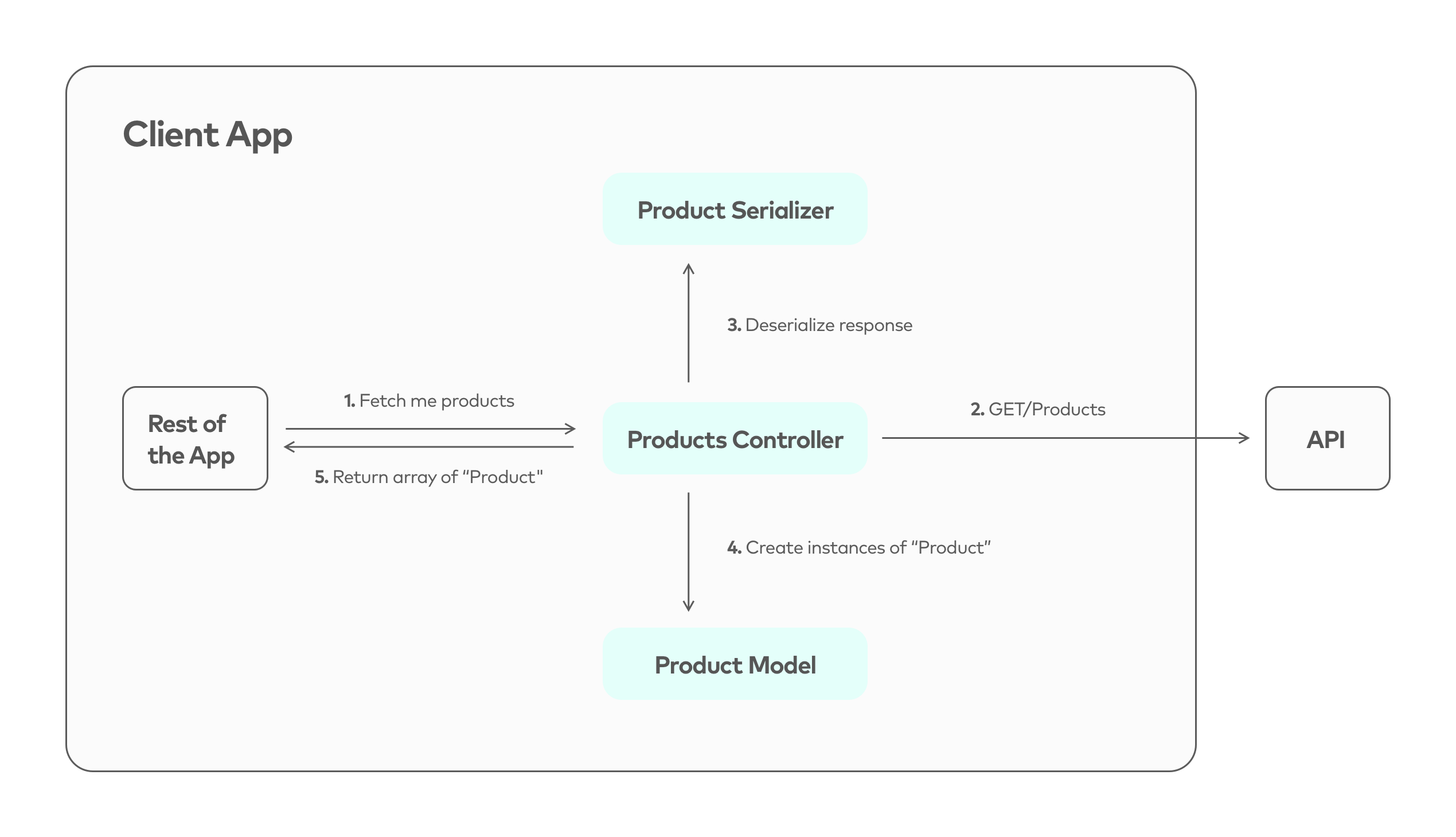

Let's start with a representation of how this pattern comes into play in an imaginary scenario. Our e-commerce needs to show products, so this next diagram represents how our frontend app would fetch them.

Let's break down what's going on and then explain what each piece of the pattern is.

- Fetch instruction: The controller is instructed to fetch products by some actor in our app (e.g. a visual component needs the info and triggers this call).

- Perform request: The controller knows where it has to go to fetch the data, so it calls the appropriate endpoint (

/productson the API). - Deserialize data: Data arrives at the controller and the Product Serializer is called upon to convert the data to be fed into the Product model.

- Instantiate models: Deserialized data is fed into Product models to instantiate them.

- Return data: Data is returned to the caller of the controller as an array of Product.

At first glance, some things might not be clear. What is "deserializing" in this context? What is a model for? Let's find out.

Controllers

Encapsulation is sometimes key for success. Think about this, should a certain UI component know what the path is to fetch products? Should it know what headers to send on the request? That seems like a responsibility of some other entity. Controllers are the main point of contact with our API, and are the entities that know how to make a certain request.

In this particular scenario, our ProductsController is the one that knows how to do all product-related requests to our API.

A certain component that wants to get products from the API must only call its fetchProduct method and await results.

How the actual request is sent and how it's structured doesn't matter to the consumer.

Let's list the responsibilities of a controller:

- Query the API as it expects (the correct endpoint, HTTP method, etc).

- Get data back and deserialize it (via a serializer).

- Instantiate models from the data (could be only one or a collection of them).

We'll explain serializers and models later, but let's assume we have a ProductSerializer and a Product (serializer and model respectively).

Here's a very simple code to implement our current ProductsController.

class ProductsController {

static async fetchProducts() {

const response = await makeRequest('/products');

// response.data is expected to be an array of product information.

const deSerializedData = response.data.map(ProductSerializer.deSerialize);

return deSerializedData.map(params => new Product(params));

}

}

I've defined the controller as a class with a static method because I feel it's easier to read and understand, but you can certainly implement this however you feel it's best.

Let's assume the makeRequest function is defined elsewhere and performs an HTTP request to our API.

It's pretty clear what's going on, I think.

First, the API is queried.

Then, once the data arrives, it is deSerialized by our ProductSerializer.

That resulting information is then fed into the Product model to create instances.

Now let's look at what a serializer would look like.

Serializers

Let's assume our API returns the product information in a non-ideal manner in this shape:

[

{

"Product_Name": "Electric Fan",

"Product_Price": 30,

"Product_Desc": "Spins really fast!",

"Product_Has_Stock": "true",

"Created_at": "2020-06-12T10:47:45.604Z",

"Updated_at": "2020-06-12T10:47:45.604Z"

},

]

There are a few things I don't like here:

Product_Has_Stockseems to be a boolean, but has been serialized as a string.- We don't really need to show the user the database timestamps (

Created_at,Updated_at), but they have been sent anyway. - The nomenclature used for the keys is really unusable.

This is where the serializer comes in! These structures are like a "firewall of data". They can remove or modify information to adapt it to our frontend's needs. Here's an example of a product serializer:

class ProductSerializer {

static deSerialize(data) {

return {

name: data.Product_Name,

price: data.Product_Price,

description: data.Product_Desc,

hasStock: data.Product_Has_Stock === 'true',

};

}

}

Our serializer has taken a single product and returned a new object with only the information we need, using a key nomenclature that is easier to read, and has also changed the type of the hasStock field to boolean.

Notice how the database timestamps are nowhere to be seen, we don't need them so we just ignore them.

Serializers are great since they automatically document the data we're using from our API.

No more "do we even use this field?" questions anymore, just go to the appropriate serializer and look it up. You are the one in control!

What if, in a few months, the API decides that Product_Name should be changed to Product_name (lower case "n").

If we've been using this field everywhere in our app, then we might be at risk of introducing bugs by mass-replacing (this is quite a simple example, I know, but bear with me).

With serializers, this is a trivial issue.

Just go to the serializer and change how the name is obtained: name: data.Product_name and voilà.

Commit, open a PR and you're done for the day.

What's more, note how serializers are also resilient against changes in structure. APIs can change how the data is organized in the response JSON, but serializers can quickly be updated to just read it from the correct place. You don't need to refactor your whole app if some data is moved. Naturally, if the information you need is removed then serializers won't be of any use, you'll have to solve the problem by fetching that data from somewhere else (the controller can probably do this).

Serializers are also in charge of, eventually, serializing data to send to the API. Given a certain model, they'll serialize it so that the backend receives the appropriate names on keys and structure! This is useful, for example, if the user is allowed to edit their data, or is allowed to create a product.

What if my API is great and they return exactly the data I need with the perfect nomenclature of keys? Serializers are also useful in this case! They will still act as a protector of your data in case the API changes in the future, so I'd recommend using these no matter what.

Models

Up to now, we've seen how our controllers help us encapsulate requests to our API, and also how serializers protect our app by acting as firewalls of data. You might think that we should be done with this. Our frontend is protected and decoupled from our API as much as we can. And that assumption is... true. Models are not meant to decouple our frontend from the backend, nor protect our data. They are used to inject meaning and value into our data. Simply speaking, they are classes that represent concepts on our frontend. The advantage of models is that they are, in a certain way, owned by the frontend.

Throwing around Javascript objects everywhere is all good and fine. We can probably just grab the objects the serializer returns and use those, right? Well... what if there's a very complex logic for how to know if we should present the product as "available" or not? In our example, maybe just because the product has stock does not mean we should show it as available. Maybe it depends on other factors and data, which the API should not really care about since it's a frontend thing. That's where a product model can come in handy:

class Product {

constructor(params) {

this.name = params.name;

this.price = params.price;

this.description = params.description;

this.hasStock = params.hasStock;

// ... more parameters here eventually

}

isAvailable() {

// Complex logic here to determine if the product is available

}

}

Having a model that represents our data allows us to encapsulate business logic right along with the data itself. Moreover, it allows us to store calculated attributes (for example, data that's derived from the initial data but that we pre-compute to avoid unnecessary computations later). You might have noticed the constructor is quite silly. We're just storing the parameters that were passed. And if you look closely you'll find out that the parameters have the same structure as what the serializer creates when deserializing the data. This might seem repetitive and kinda pointless but I think it's really worth it. And the cost of implementing a model is almost zero.

One of the greatest things about models is that you no longer work with plain Javascript objects. Your data has meaning and structure now. Data logging is now a bit more clear, as I can instantly know what type of data I'm logging. If some data I'm handling doesn't have a model prototype, then I know something went wrong.

Putting all together

Let's summarize what each part of the pattern provides:

- Controllers: provide an abstraction of our API (or a portion of it) which allows other components to not care about where the data comes from and how it is fetched.

- Serializers: protect data by acting as an adapter and a firewall. They transform and remove data according to our needs, while at the same time documenting what we're using.

- Models: add meaning to our data. They aid us by allowing the frontend to inject its own logic and value to data, without needing support from the API.

Remember that the idea of the pattern is to be versatile and applicable in many different cases. I've shown a possible minimal implementation with Javascript, but you can certainly use it in other languages with any framework. As long as you have something in your code that acts as a part of the pattern, then you're implementing it! I recommend (if you want to apply it) to experiment and see what suits you best. In my experience, I've seen that people tend to make this pattern their own by implementing it slightly differently, which is awesome and helps us learn from others.

Error handling

We haven't discussed yet how to handle errors or unhappy paths in our app. I'm not going to go into full detail, as this post is already quite packed. So I'm just going to quickly explain how we handle errors in our projects with this pattern.

Typically we implement some kind of networking service that acts as an adapter with the networking library we're using (fetch, axios, whatever you like).

In the controller we discussed above, this service would be the implementation of the makeRequest method.

When any kind of error happens, we catch it and attempt to deserialize it (this typically happens when the error has status 4xx, meaning it was a client error) to understand what happened.

The deserialized error is then thrown again to be caught by the entity that called on the controller.

That way the calling entity doesn't have to know what underlying networking library we're using, since we intercept those errors, extract relevant information and create a new error.

You could even switch networking libraries without changing anything but the networking service!

Error handling is sometimes hard, and it requires support from the backend. We must know how errors are categorized and come up with a certain "contract" for how the backend communicates these errors. This is sadly unavoidable, but using this pattern you can also protect yourself from badly formatted errors by deserializing them. Failure to deserialize an error will be interpreted as an unexpected error from the backend, and you can track those and find out what happened, even in production.

Conclusion

If I think about it, everything detailed in this post seems fairly... obvious. The pattern presented today is not revolutionary. It won't change how we develop code in a meaningful manner. But it gives a name and structure to something we typically try to implement (or at least we should!). You don't need to rediscover the wheel in each project, you merely need to remember the rules of the pattern and apply it.

There are some caveats of course ("There's no such thing as a free lunch"). Any "generic" pattern or algorithm is bound to fail or be ineffective in border cases. I certainly haven't implemented this pattern in every single possible use case. You might find it forces you to write too much boilerplate, or feel like some things you need are really hard to implement with it. But a pattern is only that: a set of guidelines to solve a pretty generic problem. You just need to take it, apply it how you see fit, and make it yours.