🧠 Introduction

In our last GenAI project, we faced some problems that we feel may be of help to many of you. The project was to build an AI agent system capable of generating new product proposals optimized for different countries and user profiles. To achieve this, the agent needed to use, among other things, a RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) component that accessed our official documents, technical reports, and product descriptions.

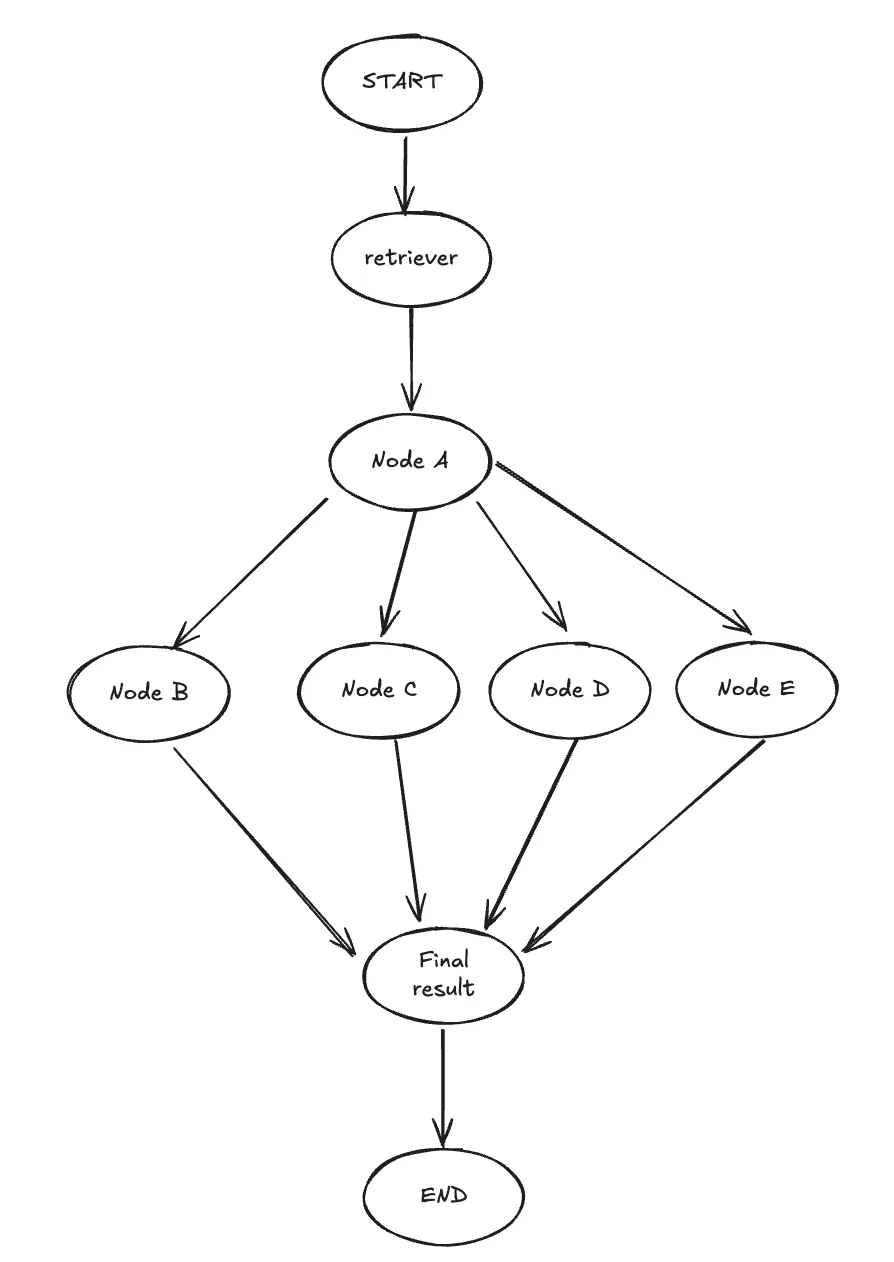

⚙️ Initial system architecture

Tools used

- Language: Python

- Frameworks: LangGraph, LangChain, LangFuse

- Infrastructure: Azure

- Vector storage: PGVector

- LLM: OpenAI

🎨 Context and modeling

We decided to model the solution as an agentic workflow because it allowed us to represent the process in a much clearer way. In our system, we had multiple data sources, different types of transformations, and variable conditions (such as country or user profile), which made the logic complex.

This type of solution allowed us to divide that logic into independent nodes. Each node represented a well-defined unit of work, and the connections between nodes explicitly defined the dependencies between tasks, which also resulted in a more organized codebase.

Graph composition

Retriever Node

In order to better understand the graph without going too much into the business logic, the Retriever node was responsible for obtaining the relevant information for the execution of the flow. For that we used an Asynchronous PGVector retriever, which consulted a vector base previously built from documents. These documents were previously processed and embedded using OpenAI embedding models.

Nodes A, B, C, D and E

- Node A generated 9 different outputs, each of which served as input for nodes B, C, D and E.

- These nodes performed further processing and, for each input received, produced a variable number of outputs - on average, about 9.

Finally, the Final Result node processed the final results.

🤖 Interaction with OpenAI.

Each node made requests to OpenAI using a system prompt accompanied by multiple inputs. These inputs could come from different data sources, people's profiles, etc. The amount of information could be very large, depending on the information the user wanted to process.

Pseudocode of the initial graph generation

add_edge(START, "retriever_node")

add_edge("retriever_node", "node_a")

add_edge(

"node_a",

["node_b", "node_c", "node_d", "node_e"]

)

add_edge(

[

"node_b",

"node_c",

"node_d",

"node_e",

],

"final_result_node",

)

add_edge("final_result_node", END)📈 Scaling the solution: First drawbacks

In simple scenarios, the system worked smoothly, even in the first releases of the system, where there were few country profiles, and little information to process, we had no problems.

However, as the volume of data grew, we ran into two problems that, combined, made the system unusable: on the one hand, the entire processing exceeded the time limit defined by Azure (we use Azure app Service, and for HTTPS requests, the connection is maintained for 4 minutes 20 seconds approximately); on the other hand, the size of the requests to OpenAI exceeded the limit of tokens of the context window (32k tokens), which made it directly impossible to process certain requests.

These two bottlenecks were related: the more data included, the greater the amount of processing required and the larger the size of the prompt, and therefore of the output. In other words, the greater the input, the worse the performance and the greater the risk that the request could not even be processed.

Faced with this situation, we decided to redesign the graph, incorporating parallelization in certain edges (represented in blue).

Pseudocode of the graph generation after parallelizing.

add_edge(START, "retriever_node")

add_edge("retriever_node", "node_a")

add_conditional_edges(

"node_a",

parallel_node_a_to_b,

["node_b"],

)

add_conditional_edges(

"node_a",

parallel_node_a_to_c,

["node_c"],

)

add_conditional_edges(

"node_a",

parallel_node_a_to_d,

["node_d"],

)

add_conditional_edges(

"node_a",

parallel_node_a_to_e,

["node_e"],

)

add_edge(

[

"node_b",

"node_c",

"node_d",

"node_e",

],

"final_result_node",

)

add_edge("final_result_node", END)each of the functions parallel_node_a_to_*, is in charge of dividing the inputs coming from node A into chunks and distributing them in parallel to the corresponding nodes (B, C, D or E). An example of implementation of this function is shown below.

async def parallel_concept_node_a_to_b(state: GraphState) -> list[Send]:

send_list: list[Send] = []

for elem in state.results_from_node_a:

for country in state.countries:

send_list.append(

Send(

"node_b",

{

elem=elem,

country=country,

}

)

)

return send_listFor this purpose, we used Send from LangGraph.

Parallelization not only allowed us to distribute the processing load and reduce processing times, but also enabled us to divide the inputs into smaller chunks, avoiding exceeding the token limit of the context window without sacrificing the text quality generated by the LLM. In other words, we were able to allow the system to process large volumes of information without breaking down in terms of time or input size (in principle).

This led to more than 400 tasks running concurrently for certain graph inputs. This parallelization not only significantly reduced processing times, but also allowed solving one of the main bottlenecks of the system: the token limit of the OpenAI context window. By dividing the inputs into smaller chunks and distributing them in parallel executions, we avoided exceeding the maximum allowed per request.

However, despite that improvement, in cases with heavy processing we still exceeded the Azure limit mentioned above. To definitively solve this problem, we implemented data streams from Langgraph, which were then sent to a websocket, allowing us to maintain persistent communication between client and server, and avoid timeout errors. This solution involved backend and frontend adjustments to adapt to the new communication model.

❌🧵 Limitations when scaling parallelization.

At the time of performing a more exhaustive testing, we noticed that we had a new bug in the system. The problem was that the logic defined in each node of the graph used Langchain to build chains, and those chains, in turn, invoked OpenAI models through the langchain-openai and openAI packages, which internally use httpx to make requests.

When we implemented parallelization, the number of asynchronous executions grew considerably -in some cases exceeding 400 concurrent tasks. It was in this context that we started to experience ConnectionError errors.

While this error was initially related to an HTTPS issue that seemed to fail with many concurrent requests, we also suspected that our Azure machine was running out of resources. Although these operations are primarily limited to I/O, handling so many simultaneous requests and network calls can also significantly overload the CPU.

We were then faced with the following dilemma:

- If we parallelized to the maximum, we would get errors.

- If we avoided parallelization, we exceeded the context window limit

- Scaling the infra would increase our costs

⚖️ Final solution: Find a balance when parallelizing.

nstead of taking parallelization to the maximum level, we decided to parallelize by grouping a certain number of elements in such a way that there is parallelization but it does not exceed the limits of the context window.

We went from 400 concurrent tasks to approximately 50. The tradeoff of this decision was that the complete execution of the graph increased by a few seconds. However, thanks to the fact that we had already implemented data streaming from LangGraph combined with WebSockets, this increase in time did not imply new errors and did not worsen the user experience.

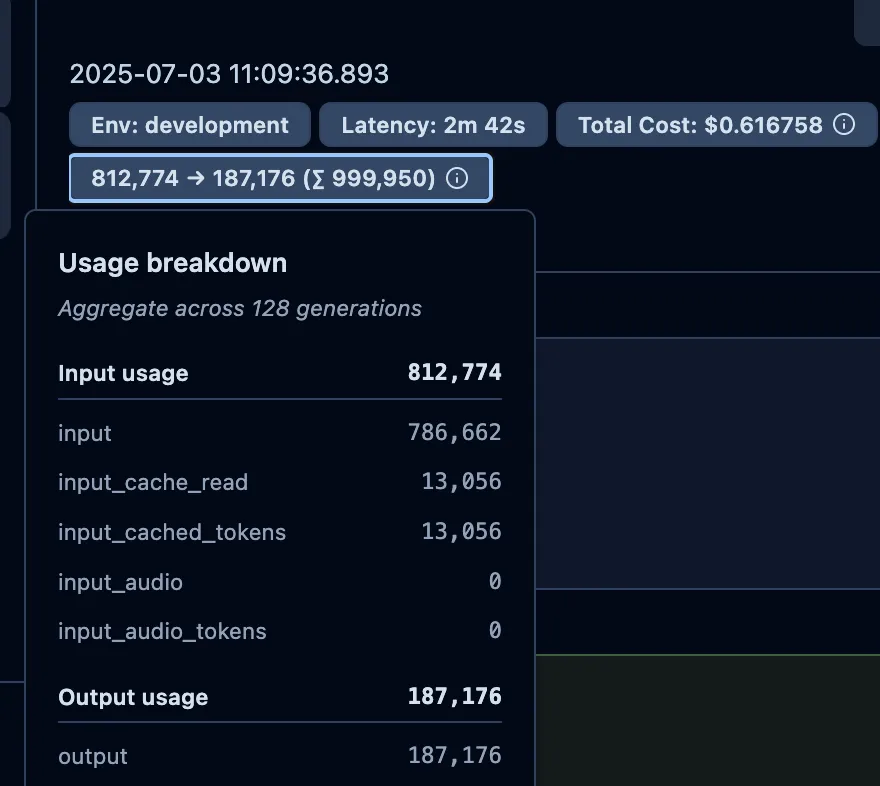

Below you can see a complete execution of the final graph.

- 812774 input tokens

- 187176 output tokens.

So we are looking at approximately 1M tokens per graph run.

✅ Conclusions

Throughout the development of this system, we faced several technical challenges that forced us to rethink our architecture. Initially, the system worked well with little information, but as the data volume scaled, two critical limitations appeared: the time limit imposed by Azure for HTTP requests and the context window token limit in OpenAI models.

Network parallelization was the first major improvement. It allowed us not only to reduce processing times, but also to split the inputs into smaller parts, thus avoiding exceeding the maximum number of tokens allowed. However, pushing this strategy to the extreme - with more than 400 concurrent tasks - brought up new bugs related to Connection Errors.

This put us in a dilemma: if we didn't parallelize, the system would fail due to too many tokens or timeout; if we parallelized too much, it would fail due to connection errors. The solution was to find a break-even point. We clustered the data and reduced parallelization to approximately 50 simultaneous tasks, which allowed us to maintain good performance without system failure.

Finally, this experience taught us a lesson: it's key to carefully design the graph, analyze the number of tasks to be executed, and the architecture of the application from the beginning.

This leads us to the next question: what if, instead of having a single machine with a fixed number of instances, the LLM logic were managed using a serverless solution? We could explore whether a service like Azure Functions offers better performance, as it would automatically manage the creation of new instances and avoid issues related to overloading the system.

Aknowledgements

Special thanks to Nicolás Hernandez for his outstanding leadership throughout this project, and to Gaston Valvassori for being a great teammate and collaborator.