Machine Learning

Precision Agriculture And The Future of Farming with Machine Learning

Maintaining a plantation, whether it’s for forestry or crops, has never been more expensive (costs per acre in the US have risen 170% since the 70s). And this is partly due to the increasing costs of maintaining weed-free fields.

Weed detection and control in small and large farms has become a challenge. Herbicide usage has increased (527 million pounds in the last 20 years), and although its price has not necessarily decreased, never have people spent more on it (a whopping $6.6 billion yearly in the US alone).

Machine Learning and Computer Vision have provided solutions to tackle the challenges producers face regarding weed control. In the following post, we’ll discuss the critical problems around herbicides and irrigation and how ML tech has helped reduce its economic and environmental costs.

The problem with weed control in agriculture

Agricultural producers have to address three main problems when facing the issue of weeds growing amongst their plantations:

- The cost it infers.

- The damage to the soil.

- Resistance of the weeds to certain herbicides (which means more costs).

Rising costs of battling weeds

Overuse or waste of herbicides has increased production costs considerably. According to the latest Cost of Crop estimation by the Iowa State University, in 2022, herbicide will account for 25% of the total cost per acre of planting soybeans (a lot compared to the 8% it represented a decade earlier, in 2012, according to the same study). It’s also increasing faster than other production costs, having almost doubled in the last decade. However, its usage has not wavered; 3 billion pounds of herbicides are used yearly.

Worst of all, the costly herbicide doesn’t always reach its target because broadcast-spraying (the most common weed control method) sometimes causes the chemical not to hit the targeted weed, landing on soil and healthy plants.

Impact of herbicides on soil

Application of herbicides can disrupt earthworm ecology, inhibit soil N-cycling, and increase disease, altering soil function. And although impacts might be minor or temporary, herbicide application is still risky. It may be a “necessary evil”, but it’s worth mentioning some of the damage it’s been proven to cause, especially if these side effects can be reduced or remedied.

The truth is, there’s also a lack of evidence of damage to the soil because there’s not a consistent framework for assessing it, there are other elements affecting soil such as management practices (crop rotation, tillage), and there's a limited amount of long term studies on the topic.

Effects on food crops are another topic entirely and one that’s been widely discussed. However, we’re focusing on side effects regarding the soil and not the plant itself.

Glyphosate-resistant weeds

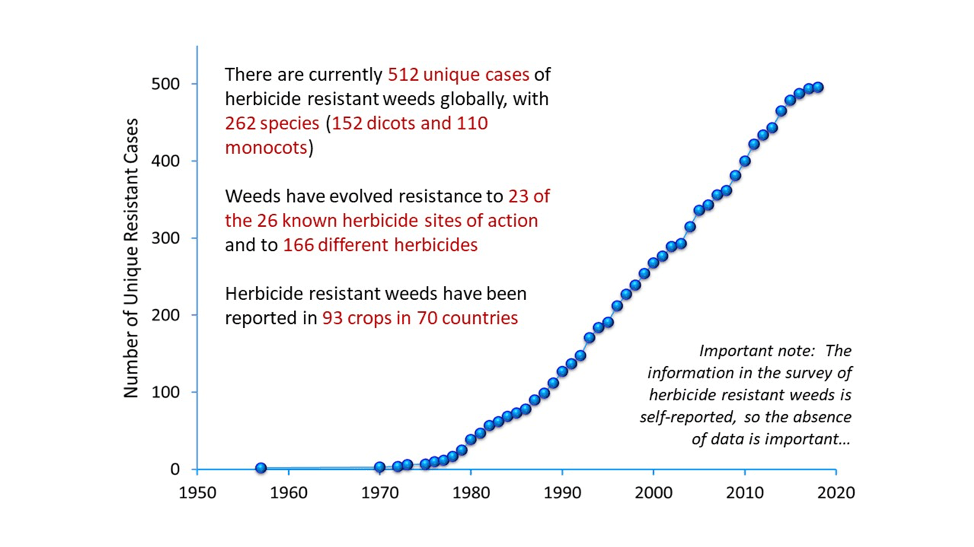

Intense and continuous use of herbicides resulted in the constant evolution of herbicide-resistant weeds, which are increasing with time. About 266 weeds resist approximately 164 different herbicides throughout 71 countries.

Glyphosate resistance is perhaps the newest and more widespread type of resistance, the introduction of Roundup Ready crops in the 90s and the constant decrease in its price made glyphosate the go-to-herbicide of the last decade (although it has been put into question increasingly over the last years). The flipside, however, is the increasing amount of glyphosate-resistant weeds.

Common treatment recommendations go from managing the intensity of glyphosate to rotating or tank-mixing it with herbicides that have different modes of action. It is also recommended to scout the field to identify the weeds and record their locations. However, this also means incurring in further expenses, as tank mixes, for example, are not usually cheap.

Image Source

Image SourceHow ML can solve these problems

The rise of deep learning algorithms and computer vision systems brought new possibilities to solve problems in an abundance of industries and fields of expertise. In this case, the design of DL models using image classification and object detection seems a natural answer to many of the problems troubling producers in agriculture.

Solutions are coming in the shape of targeted spraying tractors based on deep learning methods that process live images, locate, and classify different kinds of weeds on the soil, allowing the model to determine the best course of action for each specific case.

This solution tackles each one of the three problems stated above:

Rising costs: By identifying glyphosate-resistant plants, the machine abstains from wasting herbicides on plants that won’t respond to them or surfaces that don’t need it. Furthermore, it saves you from buying a tank mix partner like FirstRate® (which has also produced some resistant weeds) to spray along the glyphosate.

Glyphosate-resistant weeds: As we mentioned, when the weed is identified as glyphosate-resistant, other herbicides are sprayed in its place, ensuring the most effective treatment is provided.

Impact on soil: Spraying only within the weed’s space instead of in the whole plantation presents evident benefits regarding soil contamination by exposing only a small portion of it to the chemicals instead of the entire surface.

It seems this solution would solve most of the problems affecting trees or crops plantations, but it may be worth understanding how exactly you will achieve everything mentioned above. Let’s dig deeper into how they work and the technology that assures the tasks will be performed efficiently.

Object Detection for detecting and distinguishing types of weeds

Image classification assigns the image of an object with a class label (tag) and objects localization locates it within the image by drawing a bounding box around it (or them in case there are more than one). Object detection performs both tasks and produces a bounding box with the specific tag assigned to each object in the image. When the model processes the image, it can determine whether each object is a human, a dog, a cat, or, in this case, a weed that’s not supposed to be there. Just as it can differentiate a dog from a person, this model can be trained to detect and differentiate between several types of weeds. In the last decade, Computer Vision research has broadly studied object detection methods, especially since the success of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in addressing the issues.

AlexNet along with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks proved the advantages of using Neural Networks based on convolutions to perform classification tasks on images without the need to extract characteristics by hand, leaving that task to the neuronal network instead (Feature Learning) and simply taking the array of pixels as input.

The idea behind the solution is for the individual nozzles to spray the desired herbicide on the detected weed as fast as possible because tractors should reach speeds of up to 6.3 mph, and the weeds should be detected from a distance of at least 9.5 ft. The best course of action would be for the system to use object detection to identify which area of the image the weed is in and make sure if it’s reachable by the nozzle and if it’s close enough to the plants, we aim to protect (therefore not wasting herbicide in weeds that are too far away and don’t pose a threat). For real-time object detection, fast models such as Yolo and EfficientDet find Bounding Boxes around the object while tagging it in 20 milliseconds approx.

Datasets for sourcing weed and plant images

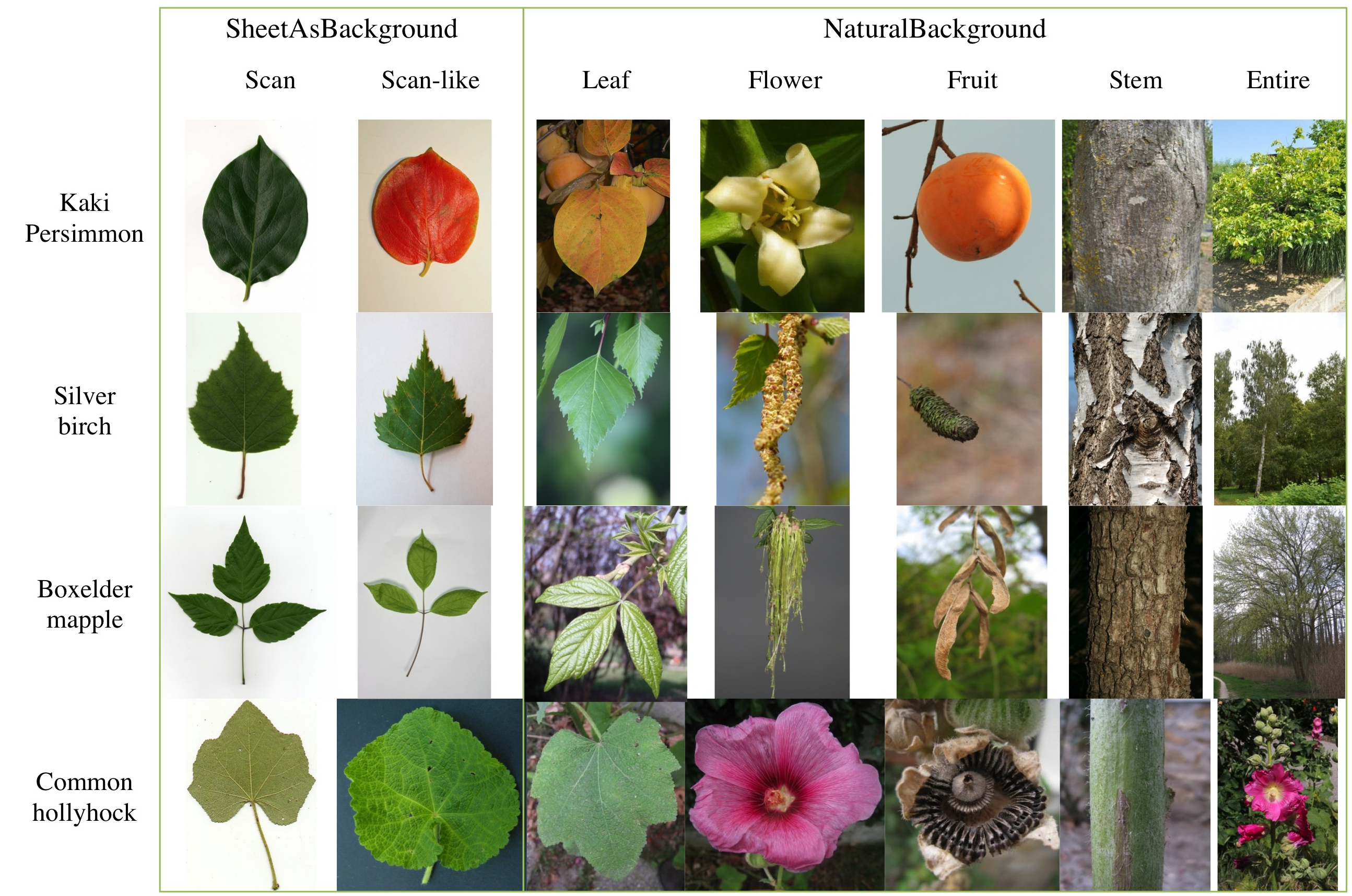

AlexNet and other models were based on ImageNet, which is one of the visual datasets available (i.e., a dataset that contains millions of images that have been classified by hand to indicate the object in the picture). But because we will be dealing with very specific images (plants/crops/trees) the ideal would be to transfer the classification knowledge acquired in ImageNet or other large datasets, to a more specific dataset. That can be achieved by Transfer Learning, which enables one to take a model trained on a large dataset and fine-tune it on a smaller dataset without having to re-train it from scratch (which would take a considerable amount of time).

So no matter the dataset you choose (MS COCO, ImageNet, etc.), you won’t have to train your model from zero to recognize and classify plant images.

This model's main obstacle is that the landscape will invariably change. Trees, plants, and crops all grow; different lights, weather patterns, branches and other objects might come loose on the ground, mud, uniform terrain, etc. Furthermore, different regions have specific plant species and weeds, making it challenging to find a solution that works with similar results and efficiency everywhere. This is where a good dataset becomes key.

An accurate dataset is achieved by creating it with all possible scenarios in mind. This is done by altering the training images of the data set with random noise, rotating it, generating symmetric images, removing small patches of it, selecting patches and discarding the rest, changing color and light, etc., as well as domain-specific alterations such as day, night, and rain simulations. This will improve the model’s performance in the changing landscapes.

Object Detection and Edge Computing for fast response

Because the ML model should perform on pre-existing software on the tractor, edge computer comes as the organic alternative. It not only improves response time and saves bandwidth, but it’s also easier to install, cheaper, and can work without an internet connection (essential if you want it to work in remote farmlands).

The advantages this solution presents are obvious, if you know exactly what weed it is you can select the best herbicide to spray depending on the weed’s resistance and save a considerable amount of herbicide by spraying it directly on the weed and not on the crop/tree. Not wasting herbicides on resistant weeds or spraying them on plants that don’t need it will invariably help save a considerable amount of costs in the long run.

Current solutions

Two ready-made solutions currently dominate the market: John Deere’s See & Spray™ developed by their acquired tech startup Blue Rivers and Bosch’s Smart Spraying, created within their Joint Venture with chemical giant BASF.

The system developed for John Deere detects weeds and automatically turns individual nozzles off and on for the desired spray length to hit just the weed. They claim this solution causes farmers to use 77% less herbicide. Their ML model is based on millions of images of weeds collected over 5+ years.

The system already comes integrated into their John Deere Sprayer, which minimizes input costs. However, it works only for fallow grounds, as it detects the weeds by differentiating their green color from the darker soil, so if you were to use it in planted terrain, the challenges would be many.

Smart Spraying works similarly to the solution described throughout the post. By using cameras and AI, their system distinguishes plants from weeds and the software automatically selects and applies the correct type of herbicide where it’s needed. Smart Spraying works similarly to the solution described throughout the post. Using cameras and AI, their system distinguishes plants from weeds, and the software automatically selects and applies the correct type of herbicide where needed. This solution is broader than John Deere’s, meaning it can be used in other scenarios besides the fallow ground. It’s also extremely fast, recognizing and spraying the weed in 300 milliseconds.

More custom solutions sometimes adapt better to systems you already have in place. Furthermore, tagging images from your field itself would be convenient because the types of plants and weeds vary in each case. A custom image library that was verified by people working the fields could be even more accurate than a ready-made solution.